Guest editorial

By: Dr. Albert D. Bates, Principal, Distribution Performance Project

This article was published in the January 2019 edition of NTEA News.

An increasingly competitive environment is causing many distributors to rethink their service profile with the idea of providing exactly what customers want. While this may lead to the conclusion that customers want lower prices, data suggests there could be something more important. The key is to identify what and how to provide it in an affordable way.

Understanding customer needs

Distributors have long since wrestled with the issue of determining what their customer set really wants. This question has been researched in multiple lines of trade with amazingly consistent results.

About a dozen years ago, I was commissioned to examine the existing service profile of distributors — more specifically, to identify additional services that would strengthen customer loyalty.

The results were surprising, as almost no customers desired added services. Instead, they wanted distributors to offer a broader selection of products and for those offerings to be in-stock more often.

As it turns out, this was not a one-off finding. Research across multiple lines of trade produces an almost identical conclusion. Customer needs from their distributors can be put into the following hierarchy — from most to least important.

- In-stock — Having items available when needed.

- Depth of assortment — Facilitating one-stop shopping with an array of items.

- Delivery speed — Providing merchandise on a real-time basis.

- Order accuracy — Eliminating errors in order picking and billing.

- Price — A fair, as opposed to the absolutely lowest, price.

Despite being last place in this ranking, price is invariably regarded as being more important. A potential reason for this is because many companies have an almost identical service profile with regard to the first four items. Therein lies the opportunity. Giving customers greater certainty on the first four can somewhat negate the very real price pressures in today’s economy.

Economics of need fulfillment

Enhancing in-stock position and depth of assortment could have an important impact on sales volume. A key concern, of course, is whether the more-inventory-for-more-sales tradeoff is advantageous economically.

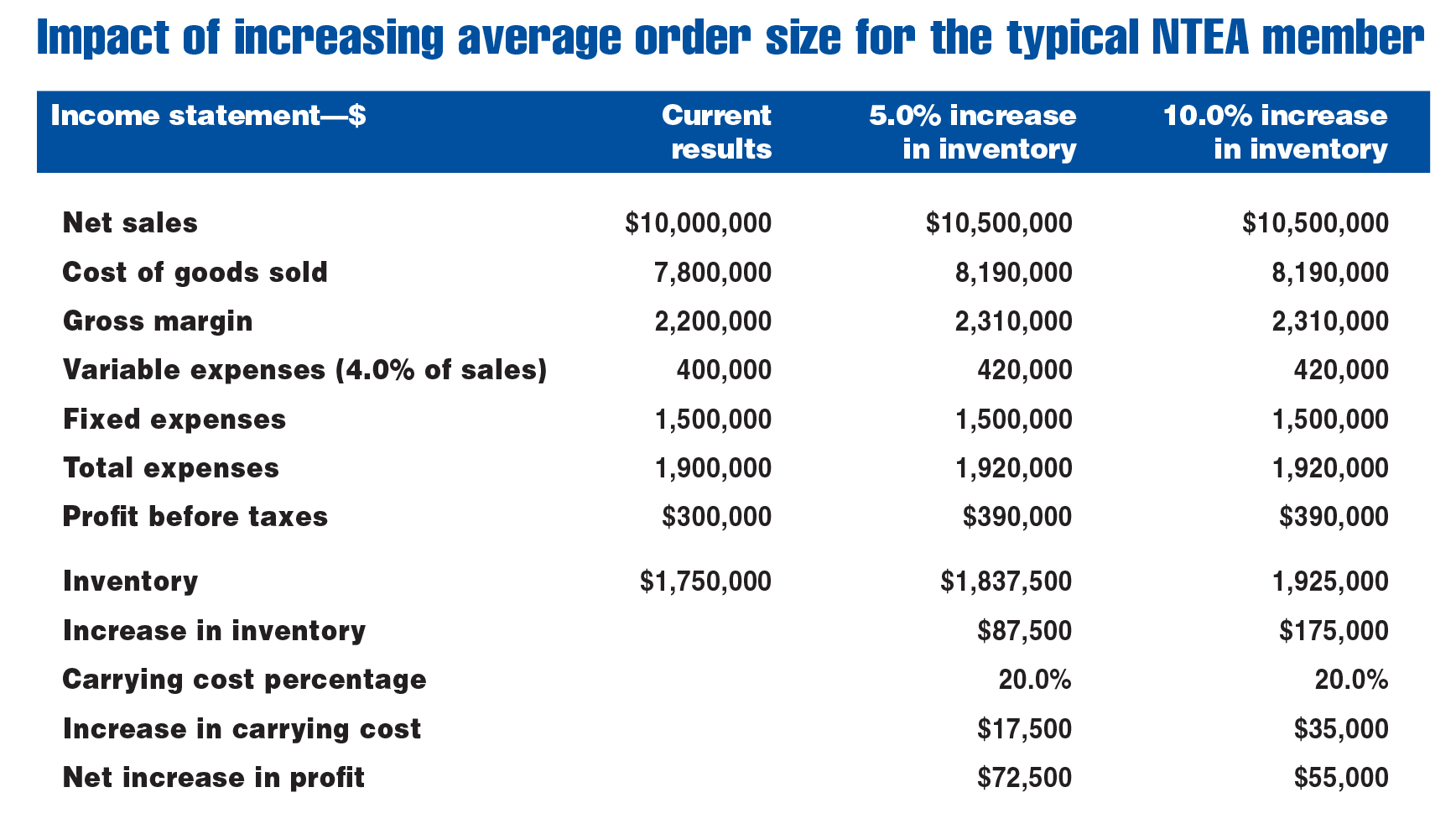

The chart above looks at the economics of a typical NTEA member business. In this scenario, the firm generates $10,000,000 in sales (shown in the first column of numbers); operates on a gross margin percentage of 22.0 percent of sales; and produces a pre-tax profit of $300,000 or 3.0 percent of sales. This requires inventory of $1,750,000.

Any effort to increase sales can take two paths — try to generate more orders or make each order larger. Both can be effective, but only the second helps address the key customer need.

The next two columns of numbers reflect the impact of 5.0 percent increases in average order size. There is no jump in number of orders — simply an increase in the size of each order. Ideally, inventory expansion, through a higher fill rate and more extensive assortment, would lead directly to this increase. It’s the payoff from meeting the first two customer needs.

With the growth in average order size in this example, dollar sales expand by 5.0 percent and operating costs are affected. Specifically, variable expenses (commissions, increased order handling and delivery, etc.), which are assumed to be 4.0 percent of sales, rise along with sales. While variable expenses increase, fixed expenses (rent, depreciation, etc.) do not.

The net impact in this scenario is a major increase in profit — from $300,000 to $390,000. This $90,000 growth represents a 30.0 percent gain. If there was no inventory increase, the entire rise in profit from operations would go directly to the bottom line. However, inventory will likely increase.

The last two columns reflect the mitigating impact of a jump in inventory. The middle column assumes inventory investment rises at the same 5.0 percent rate as sales. In this case, inventory increases from $1,750,000 to $1,837,500, or $87,500.

The bottom of the column assumes an inventory carrying cost of 20.0 percent of inventory growth, which means carrying the additional inventory cuts into the profit increase by $17,500. While a sizeable number, it still results in a net profit gain of $72,500.

The final column assumes inventory goes up twice as fast as sales (a 10.0 percent jump). Even in this extreme case, the cost of carrying more inventory is $35,000. In this example, the company would still come out ahead by engaging in the tradeoff of carrying more inventory to meet customer expectations.

The chart reflects a reality that has been true in distribution for many years. Namely, the risk associated with increasing the inventory investment to drive higher sales volume has the potential to be rewarded.

While an increase in investment such as the $175,000 in the last column may be viewed as difficult to manage, keep in mind it’s a one-time increase. The $55,000 boost in profit, in sharp contrast, represents annual, ongoing improvement potential.

Moving forward

The competitive environment is not likely to ease anytime soon. In addition, distribution, in every line of trade, is a mature business. These two factors combine to suggest steady sales growth could be a key profit driver.

Generating sales growth involves a number of important issues — and one of the most essential is providing the services customers really want.

Albert Bates, principal of Distribution Performance Project, will present Five Essentials for Profit Improvement on March 5, 2019, from 3–4:15 p.m. at The Work Truck Show®. This session will share actions distributors can take to generate higher levels of profitability as well as free tools to help with implementation.