By Steve Latin-Kasper, NTEA Director of Market Data & Research

Meet our experts

This article was published in the April 2020 edition of NTEA News.

Key highlights

- IHS Markit’s forecasts for the U.S. economy and commercial truck registrations are being revised downward for 2020, but the impact of coronavirus will not be permanent.

- Global economic deceleration will likely keep putting downward pressure on metals prices in the first half of 2020.

- National Association for Business Economics predicts housing starts will continue slowly increasing throughout this year.

Economy

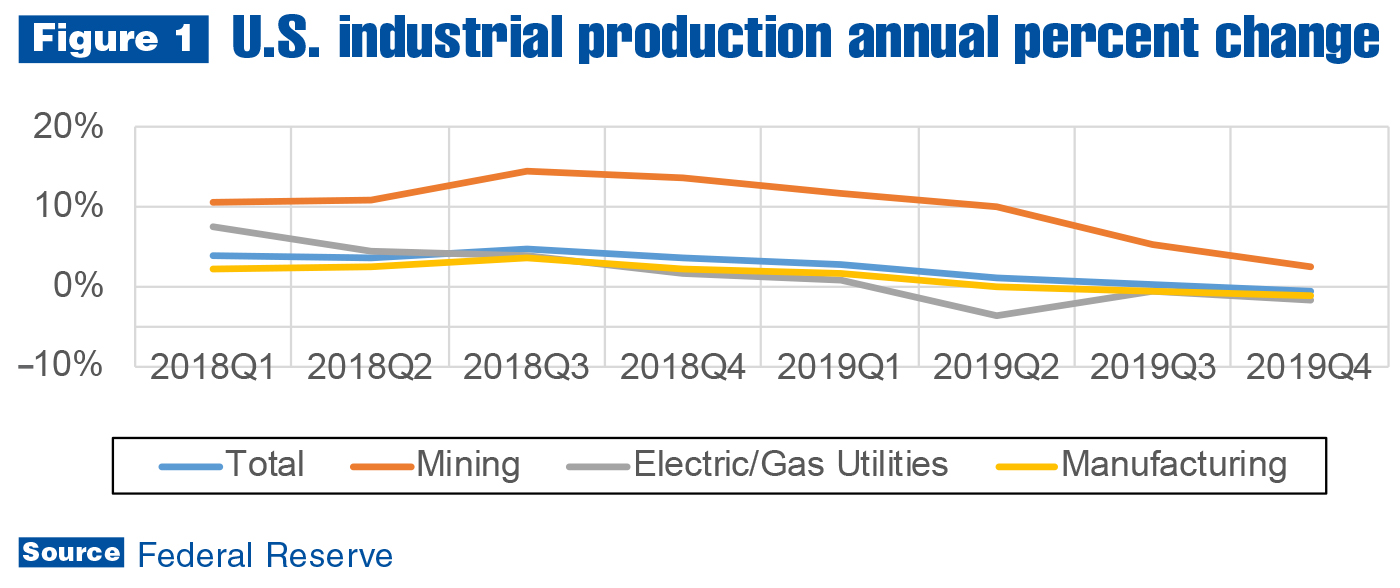

The fourth-quarter slide in commercial truck chassis sales, as detailed in the work truck industry section below, mirrored what was happening in other segments of the U.S. economy. As shown in Figure 1, total industrial production was negative for the year, as a result of manufacturing and utility sector declines. Construction expenditures (not included in the graph) were also down from 2018. Mining sector productivity held up primarily due to continued oil and gas industry growth — but this may change in the second quarter.

A key reason for fourth-quarter U.S. economic growth was that consumer and government expenditures kept increasing, albeit, slowly. The economy probably continued growing in the first quarter of this year, although at a lower rate, as the COVID-19 pandemic began to have a negative impact on growth in March. The 2020 forecast for consumer expenditures remains positive; however, forecasts for anything regarding U.S. and global economies are all being revised as of March.

As of mid-March, it’s difficult to predict how significantly COVID-19 will impact U.S. and global economies. It’s clearly having a more substantial effect on Asian economies, but trading partners around the world will experience supply chain disruptions. In the U.S., supply disruption due to difficulty obtaining parts from foreign sources has not been a major issue, but is getting worse. More importantly, as a result of school and business closures, employees who would normally be working may not be able to do so, given the current circumstances. The cumulative impact will likely be slower production throughout the economy, and also create the potential for additional domestic supply chain disruptions.

It’s clear the U.S. government and Federal Reserve are concerned about the potential negative impact. The Fed changed course regarding interest rates the first week of March, enacting an emergency 0.5% cut in the federal funds interest rate to help motivate additional loan activity and stimulate the economy. That was followed by another cut a week later, which pushed the federal funds rate close to zero (less than zero after adjusting for inflation). However, it may have a limited impact. Consumers probably won’t borrow money due to economic uncertainty generated by coronavirus. And if consumers aren’t spending more, businesses won’t, either.

To the extent additional spending is motivated, homeowners will probably refinance mortgages, which will offer additional spending power — but they’re more likely to pad their savings accounts. Business owners could take advantage of cheap money to top off inventories of intermediate inputs, but that’s the equivalent of betting they’ll be able to turn additional inventory before having to pay taxes on it. In other words, the interest rate cut may not add much to economic growth.

U.S. Congress is joining in by using fiscal policy to boost the economy. It’s debating making cash payments to all adults, and/or a temporary reduction in payroll taxes. Since cash payments will have a faster and greater impact on the economic multiplier, Congress will likely implement that idea, which comes with the same caveat as lowering interest rates — the actual economic impact will likely be minimal. The reason is, most of the cash payments will be used to pay mortgages/rent, utility bills, and other monthly payments that would have been made anyway. For most families, there will be little or nothing left to contribute to growth. In summary, cash payments may not prevent recession, but will have a positive impact on the depth and length of one.

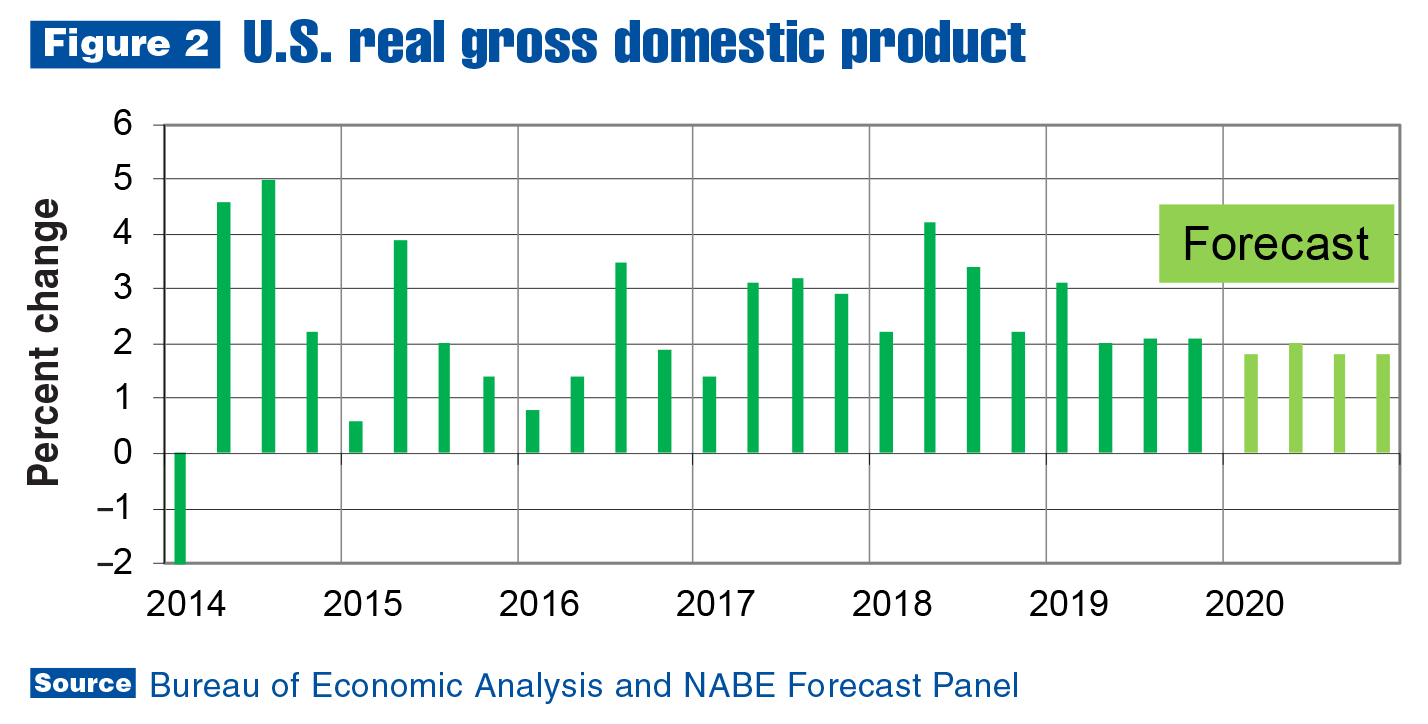

It’s important to note, as illustrated in Figure 2, the U.S. economy was decelerating well before COVID-19 came along. Some economists were predicting the country would slide into recession, or at least a period of stagnation, by the end of this year or early 2021. The virus just increases the probability of recession, and may cause it to occur sooner than it would have otherwise. The most recent forecasts are now indicating U.S. and global economies will slide into recession in the second and third quarters of this year. As of now, recovery is expected to begin in the fourth quarter. Obviously, that will depend on the extent the virus spreads. Transmission is just beginning in many countries around the world.

Work truck industry

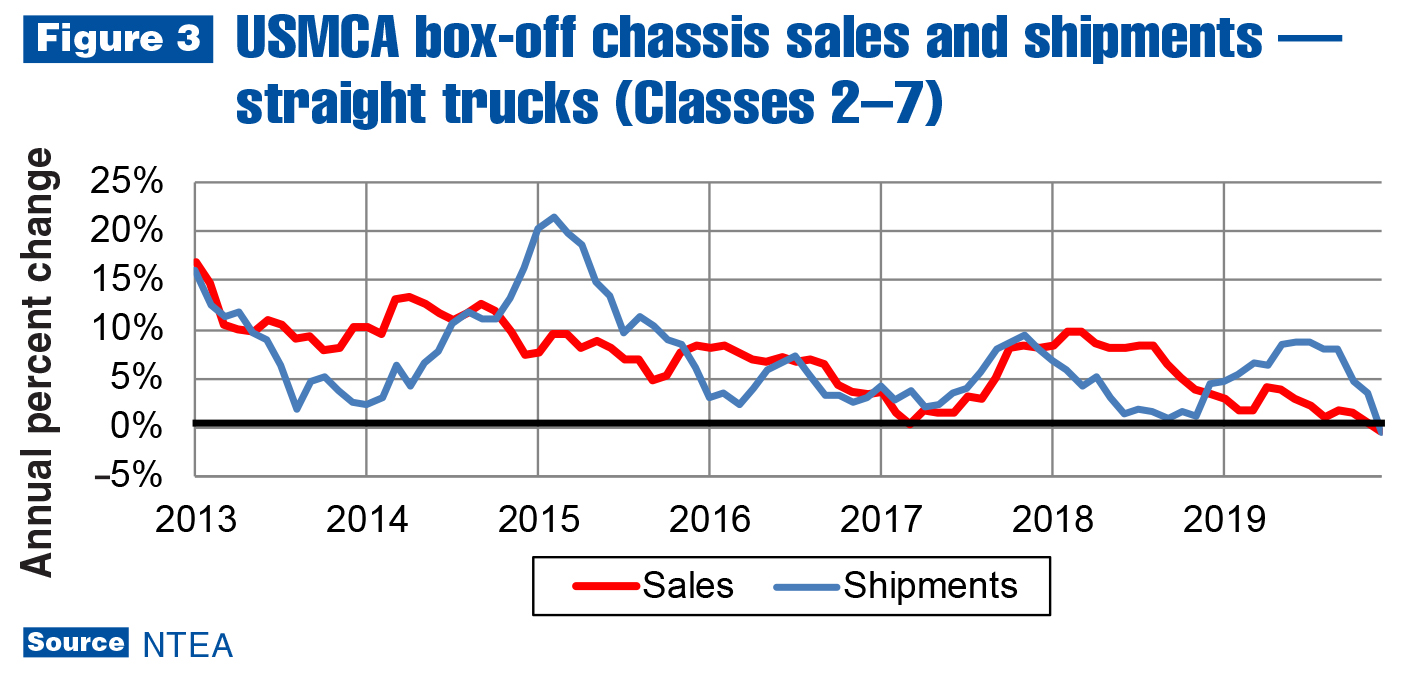

The U.S./Mexico commercial truck chassis market ended the year on a low note with a 6.9% sales decline in December 2019 as compared to December 2018, which contributed to a 6.3% fourth-quarter drop. For the year, chassis sales registered a 2% gain.

In Canada, chassis sales fell even further in December 2019, at an 8.7% rate as compared to the same month in 2018. This pulled the fourth-quarter rate down to –5.7%. For the year, sales rose a scant 0.4%.

Work truck industry sales and shipments were moving in the wrong direction at the end of 2019, obscuring the fact that it was a record (or near record) year in many market segments. In total, U.S./Mexico sales increased 2.0% in 2019. Sales rose in conventional, cutaway and low-cab-over-engine segments, and while strip sales fell 6.4%, they started growing again at the end of the year.

Figure 3 shows Class 2–7 sales decreased slightly last year; however, it was just one weight class responsible for the decline. Class 3 sales dropped 15.8% in 2019, but sales rose in all other weight classes. Class 3 has been the largest for years, and nearly remained so in 2019 after sales fell about 14,000 units from the 89,154-unit record reached in 2018. Classes 5 and 6 registered higher unit sales than Class 3 in 2019, but not by much.

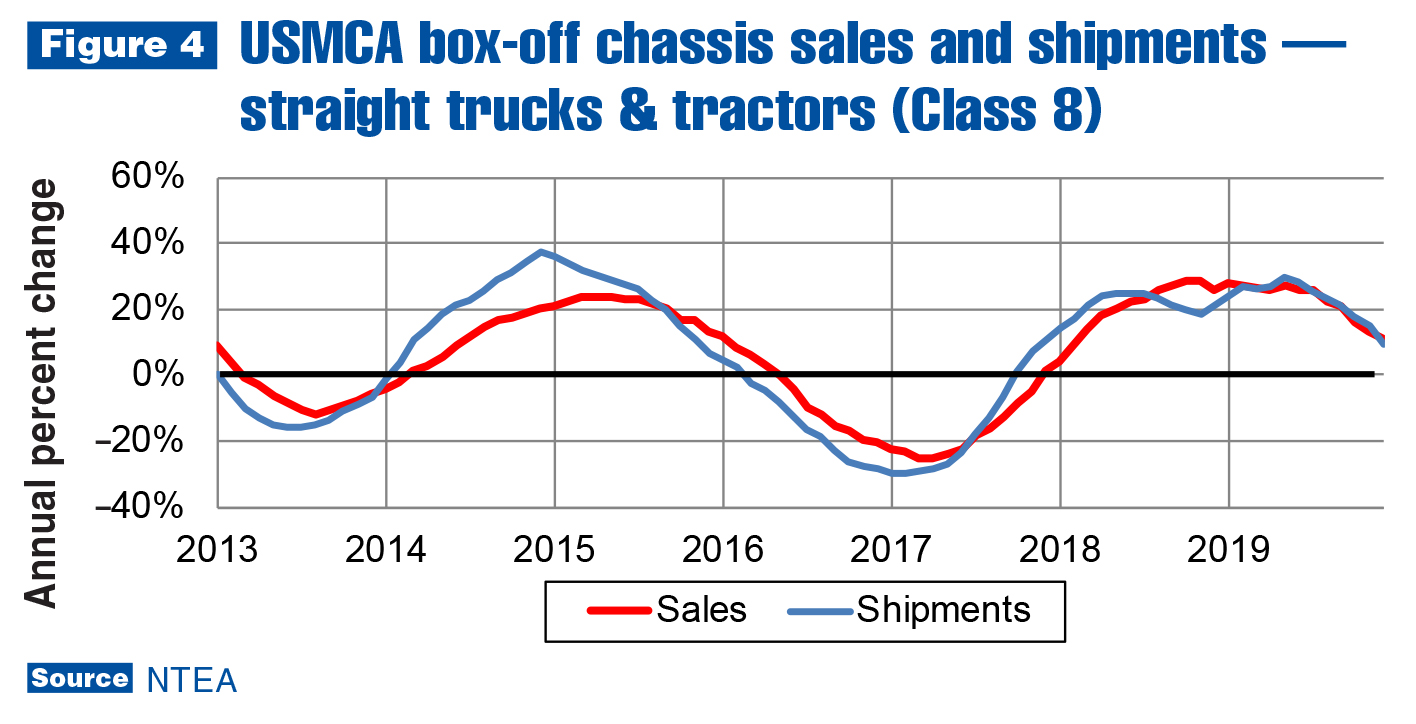

In Class 8, sales continued increasing last year, but the growth rate fell substantially

at the end. After rising about 23% in each of the first three quarters, the growth rate just cleared 1% in the fourth. For the year, sales rose 16.5% — the best performance of any industry segment in 2019 — but expectations are low for 2020 and 2021.

In the tractor segment, sales grew in the first three quarters of 2019, but dropped sharply at the end of the year. They were up about 20% as the third quarter ended, but a 13.5% decline in the fourth dragged the annual growth rate down to 9.8%. Tractor sales are predicted to decrease about 20% in 2020.

Commercial vans (Classes 1–3) far outperformed the Class 2–3 chassis segment in 2019. Sales increased 13% last year, largely due to Amazon’s fleet expansion, which resulted in a 27.7% gain in the third quarter. In the fourth, the growth rate decelerated to 4.2%, which was in line with most of the rest of the industry.

If people continue to decrease the frequency of their outings due to coronavirus concerns, there will likely be increased demand for home delivery. According to Digital Commerce 360, 82% of U.S. households already have an Amazon Prime account. Growth could come from Prime accounts being used more than in the past, and there are plenty of competitors in the last-mile delivery space. This may lead to more commercial van sales. There are upper limits to growth, though, as finding drivers will probably remain challenging.

This isn’t deterring Amazon, which announced in March it wanted to hire an additional 100,000 employees to work in its distribution centers and as drivers. Other industries’ labor losses could be Amazon’s gain. The U.S. has one of the global economy’s most mobile labor forces. Moving through the second quarter, we may experience some of the largest shifts in employment from industry to industry in U.S. history. It will be interesting to see the percentage of people who move back to their previous jobs when this is all over. There will likely be upward pressure on wages during each shift.

COVID-19 is expected to have a net negative impact on the work truck industry this year. At the time of this article’s publication, IHS Markit is revising its forecast for 2020 commercial truck registrations. The current forecast calls for a roughly 10% decline, which may be further revised as additional data becomes available.

Metals and energy prices

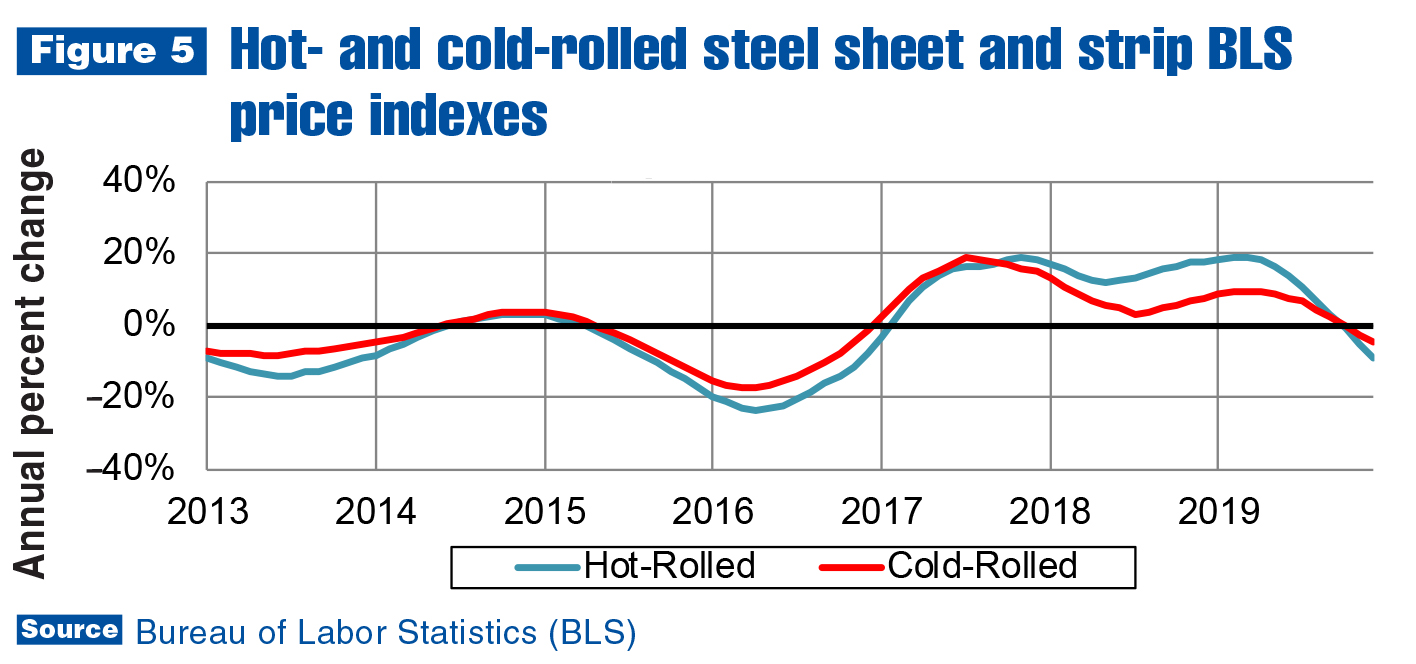

Global economic deceleration will likely continue putting downward pressure on metals prices in the first half of 2020. Coronavirus effects may cause an actual recession in China, and since it’s the world’s largest consumer of steel and aluminum, that downward pressure could be worse than expected the first half of this year. As shown in Figure 5, hot- and cold-rolled steel sheet/strip prices were already falling on an annual percent change basis as of fourth-quarter 2019.

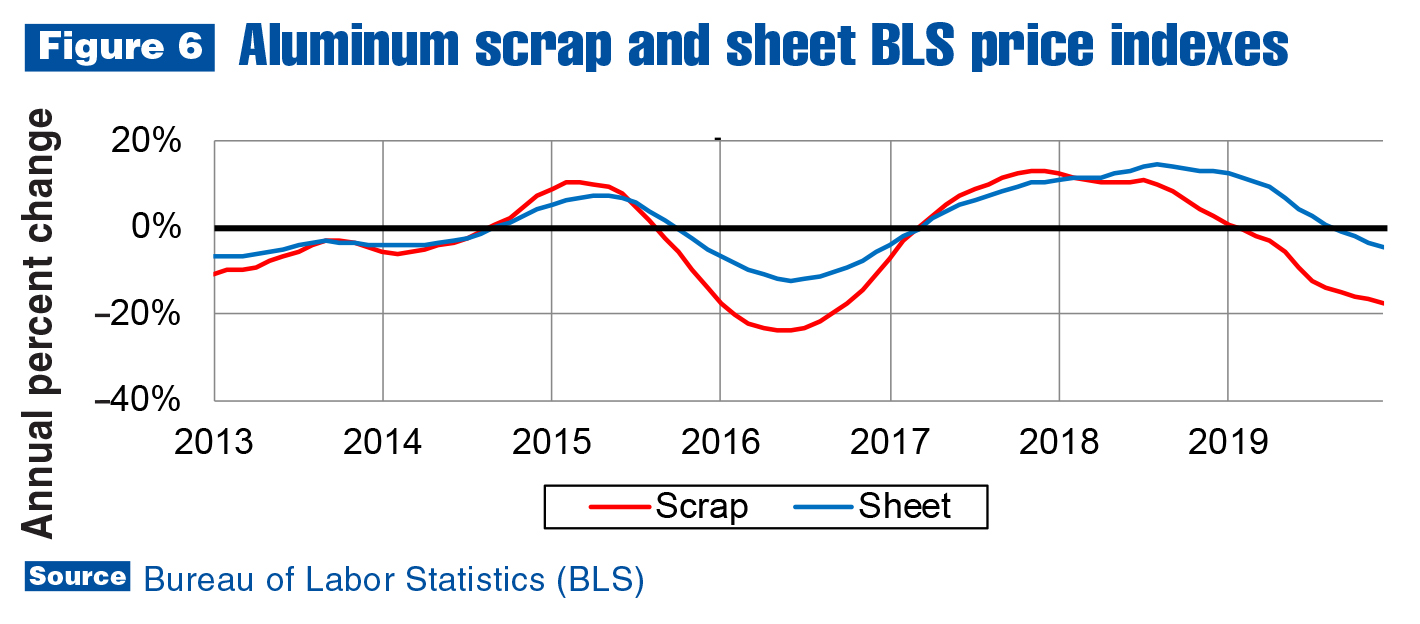

Aluminum sheet prices also started dropping in 2019. If COVID-19 runs its course in the same manner as a typical flu, and Chinese and global economies begin growing again in the second half of the year, there could be a reversal of current price trends in metals markets. If this occurs, though, it will likely be short-lived. As noted, steel and aluminum prices were decreasing prior to the impact of coronavirus, so even if COVID-19 was out of the picture, all of the issues negatively impacting metals markets — most importantly, global overcapacity — would remain. Therefore, steel and aluminum prices are anticipated to fall further in 2020.

As of early March, global oil market prices were falling sharply, but it had little to do with coronavirus. Longer-run trends were in play, and international politics had a greater effect on global oil supply. Saudi Arabia appears to have entered a price war with Russia. Two of the top three oil producers flooding the global market had a massive impact on the price of oil.

The Brent spot price fell to about $38 per barrel as of March 10, and WTI dropped to about $35. The price differential is usually about $6 or $7, so the fact that it tightened to just $3 indicates global oil traders feel the U.S. is a bit more insulated from Saudi and Russian production increases than the rest of the world.

Russia’s cost of production is about $50 per barrel. Saudi Arabia has a different problem — production costs may be as low as $10 per barrel, but oil sales fund roughly 80% of its government spending. As a result, it’s unlikely either country will persist in flooding the market beyond the second quarter.

Leading indicators

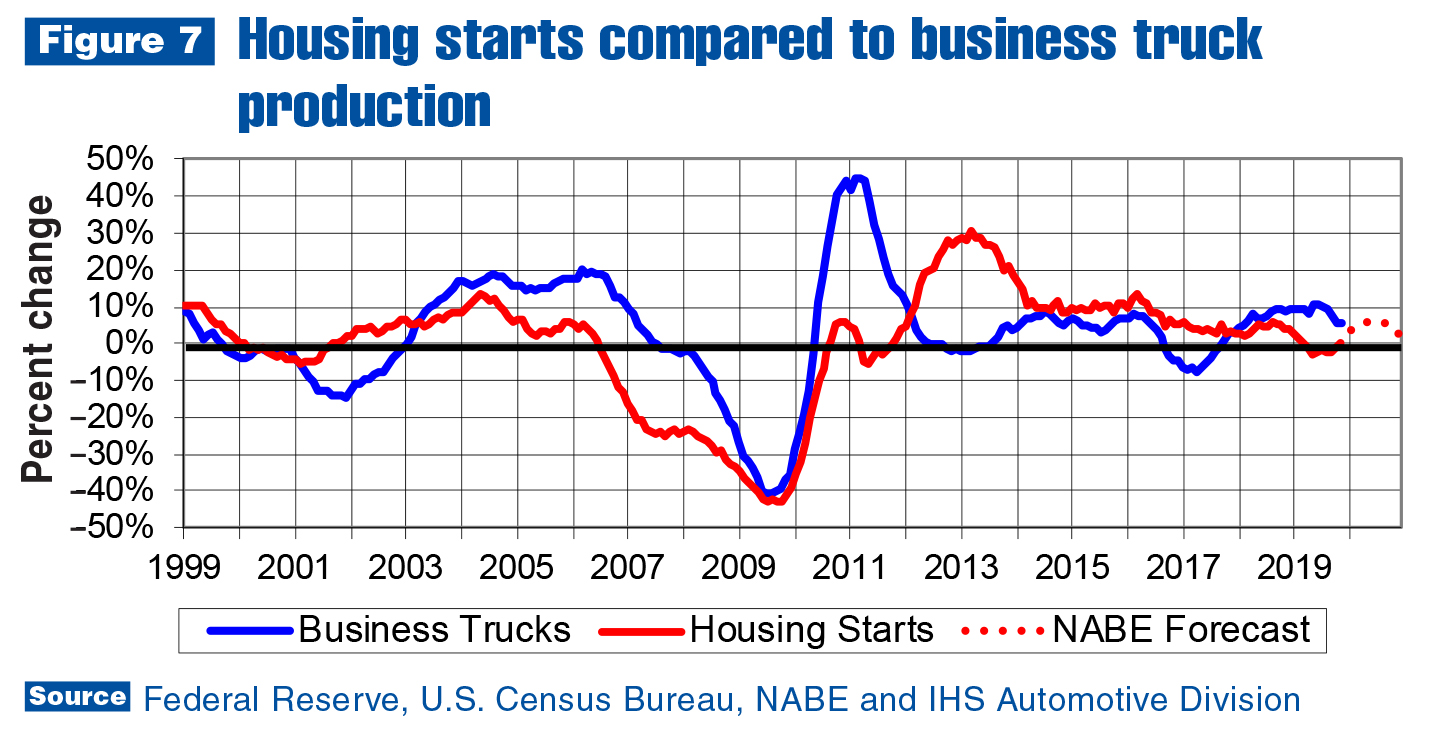

Figure 7 on shows housing starts have been trending up recently. This is primarily attributed to millennials wanting places of their own to raise their children. Affordability remains an issue, but rising incomes and lowered interest rates have enabled enough of them to buy houses so that starts are rising on a SAAR (seasonally adjusted annual rate) basis. The National Association for Business Economics (NABE) Outlook currently predicts starts will continue growing throughout this year. As of March, the virus is exacerbating the difficulties contractors are having finding employees. That will slow construction, and likely have a negative impact on growth.

Over a long period of time, housing starts has been a good leading indicator of Class 2–7 chassis sales. Intersections of the two series have usually been a solid predictor of the next turn in the chassis sales cycle. As chassis sales head down in 2020, the data series will likely intersect housing starts in the second quarter. This means annual chassis sales growth could reach its cyclical trough toward the end of the year. Class 2–7 sales are expected to start growing again in the second half of 2021.

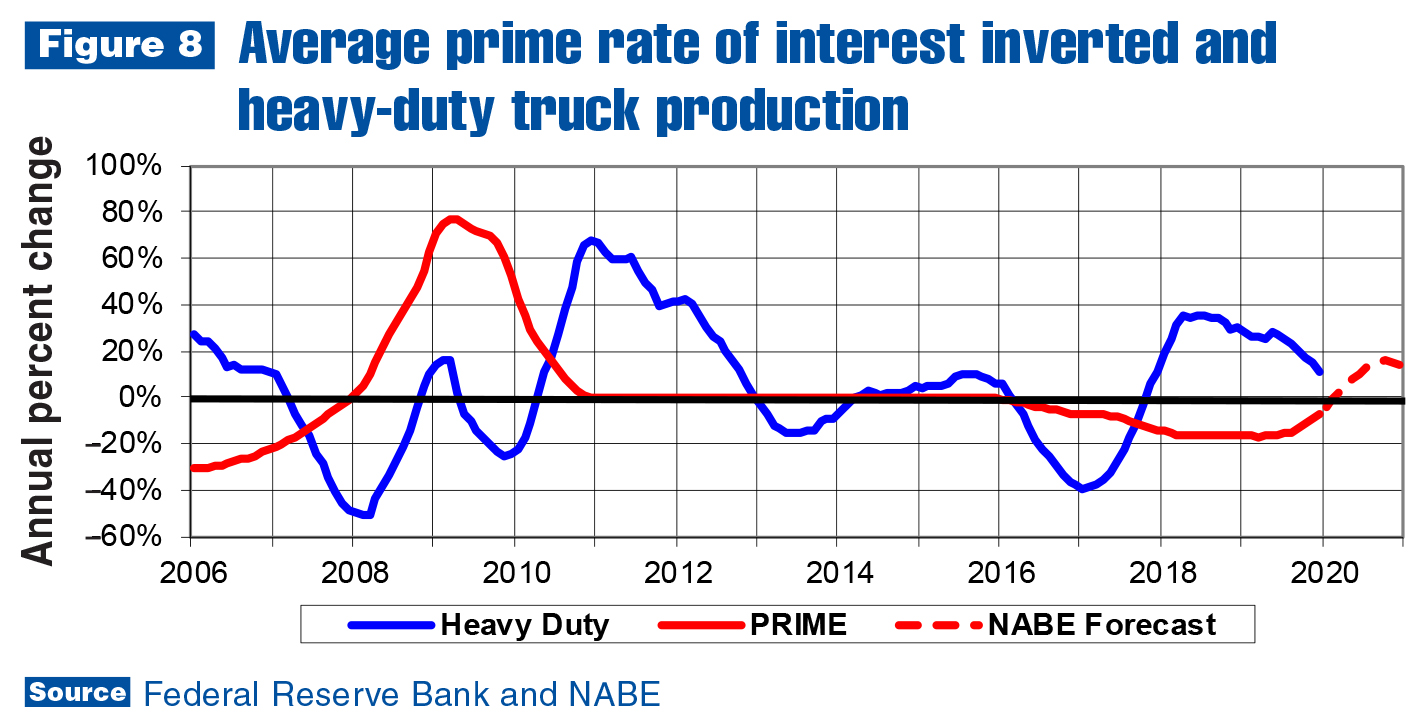

Figure 8 provides a clear estimate of the Class 8 market in 2020 and 2021. Intersections of annual percent change in Class 8 sales and average prime rate of interest inverted (PRIME) have accurately called turns in the Class 8 cycle for the last five cycles.

At the end of 2019, it appeared the two data series would intersect near the end of the first quarter. The Class 8 series trough usually occurs about nine to 12 months after the intersection, and then it takes another nine to 12 months to return to zero and positive growth. This is in line with IHS Markit’s current forecast, which calls for Class 8 sales to fall in 2020 and 2021 and start growing again in 2022.

IHS Markit’s forecasts for the U.S. economy and commercial truck registrations are being revised downward for 2020, but the impact of coronavirus will not be permanent. It will run its course, and given the flexibility of the U.S. economy, recovery could be substantial. That being said, when normality returns, the tight labor market will remain part of it. “Normal” economic growth will likely continue to be lower than post-World War II average growth.

For more industry market data, visit ntea.com/marketdata.