Guest editorial

Dr. Albert D. Bates, Principal

Distribution Performance Project

This article was published in the April 2020 edition of NTEA News.

Commoditization is one of the most widely discussed terms in distribution today. The issue suggests a new era in which companies face margin declines that make profitability challenging. Worst case, such price pressures call into question the survival of more than a few businesses.

Despite this widespread discussion, no one has really addressed the extent to which commoditization will impact profit or whether or not it will even occur. Is it permanent or simply a recurring issue that will pass?

Profit impact of price pressures

Commoditization pressures work through distribution in two often-interrelated ways. First, sales may fall if the firm does not meet price competition directly. Second, margin dollars may fall if the company responds directly to the pricing challenge. While these pressures can interact, it’s useful to look at them independently.

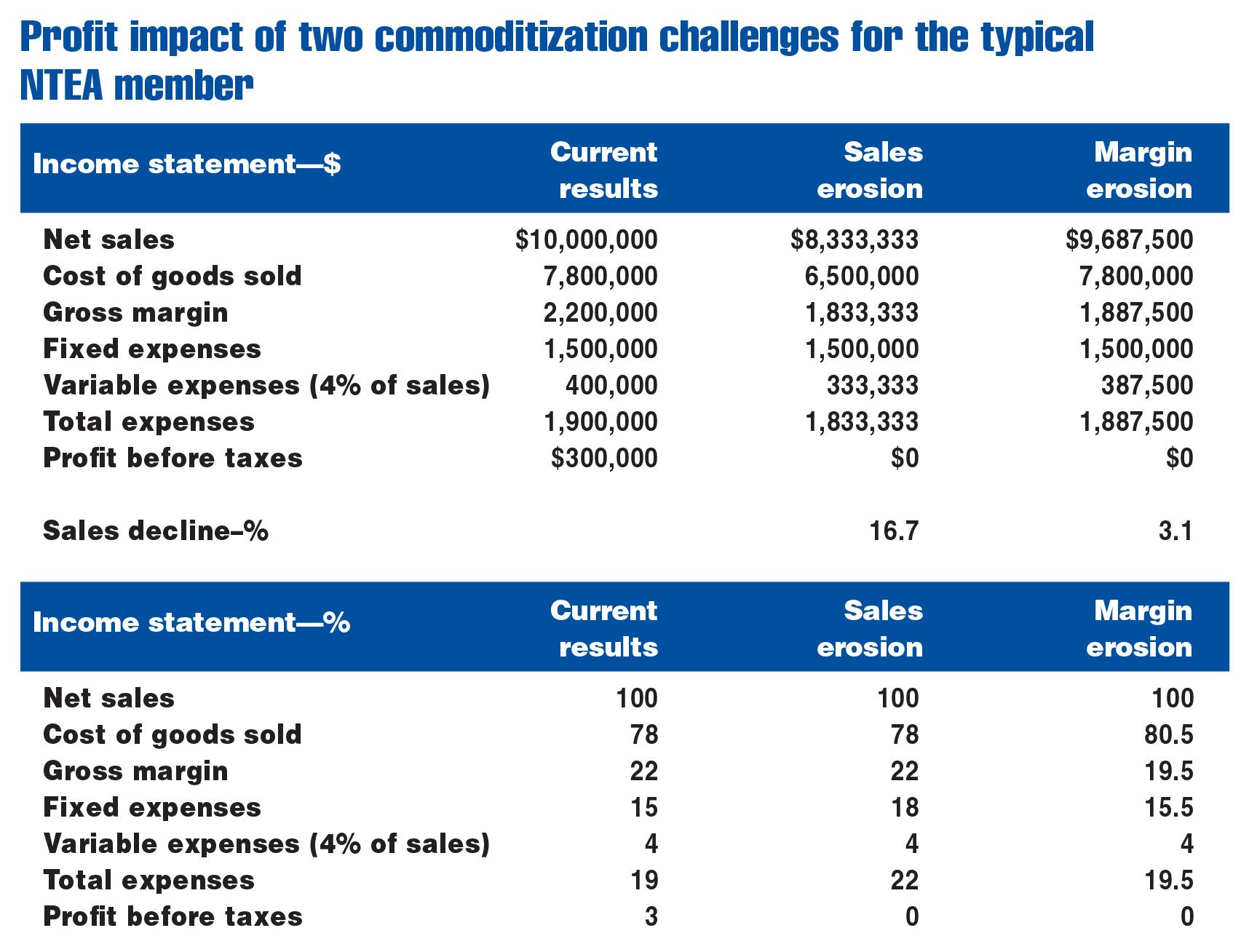

The chart above examines both scenarios for the typical NTEA distributor member. As shown in the first column, the business generates $10 million in sales, operates on a gross margin of 22% of sales and produces bottom-line profit of 3% of sales or $300,000.

To understand how sales and margin changes work through the company’s profit structure, segment expenses by fixed and variable components. Fixed expenses are overhead that will not fall if the firm faces a sales or margin decline. Clearly, if there’s a massive drop, any and all expenses can change. However, in the short run, the firm will incur these expenses, even in a deteriorating sales environment.

Variable expenses, such as sales commissions and bad debts, will change automatically along with sales during the year. They tend to be a relatively consistent percentage of sales.

Fixed expenses for the typical NTEA distributor member are assumed to be $1,500,000 while variable expenses are 4% of sales. These are only estimates, but represent a serviceable approximation.

The last two columns look at profit implications of a sales or gross margin decline. In each instance, analysis identifies how much of a change would cause the business to move to break-even, where profit is eliminated.

For the sales decline column, the first three lines on the income statement (sales, cost of goods sold and resulting gross margin) all decrease by 16.7%. Fixed expenses remain the same, while variable expenses are still 4% of sales and therefore fall by 16.7% — the same as the sales decline. As a result, profit falls to zero — the break-even point previously mentioned.

For the price-cutting scenario in the last column, sales only fall by 3.1%. However, the entire sales decline is due to cutting prices, not losing physical sales volume. Therefore, cost of goods remains the same. As a result, the 3.1% sales decline due to price cuts also causes profit to disappear.

In these examples, the profit impact of losing gross margin is more severe than the result of losing sales. Both are not good, but gross margin is a more sensitive profit driver than sales volume.

Meeting commoditization head-on

If the two options associated with commoditization aren’t ideal, a third way could involve positioning the firm so that price pressures are eliminated or at least negated. Two key actions support this option.

Account selectivity

Work done by a wide range of analysts suggests approximately 20% of all customers, across a range of industries, are almost pure price buyers. For these accounts, commoditization inevitably leads to the quest for ever lower prices across the entire product line.

Another 20% of customers are heavy, but not pure, service buyers. Commoditization will likely only modestly influence their buying decisions. They don’t not want to overpay, but need real service.

That leaves 60% in the middle who vacillate between service- and price-based decisions. To retain this customer set, companies could consider providing a service profile that justifies “fair” prices.

Theoretically, by staking out a strong position among service-oriented and mixed buyers, some firms may be able to afford to lose pure price buyers and still thrive in the commoditization world. However, a share gain is important.

One consideration for gaining share here could involve a service analysis or intensification effort, such as reviewing any services that may not be needed and maintaining an outstanding service profile on all others. It’s also helpful to ensure the sales force has resources needed to be solutions-focused for customers.

Slower-selling items

The slowest selling 5–10% of SKUs are typically bought infrequently and are low-price, why-worry-about-it-type items. Their availability can be value added, even among price-sensitive customers.

There may be concerns these items will be perceived as overpriced, but price perceptions are not built on these products. Many price perceptions are built on the fastest-selling items in the product line. A large factor in slower-selling item success is availability, not necessarily price.

Moving forward

Commoditization represents a real-world challenge for distributors. With almost everything available for purchase online, price pressures can be an even greater obstacle. However, price has never been the only thing distributors have to offer. A strong service profile, tailored to key customer needs, can help companies maintain and even gain market share.

For more industry profitability resources, visit ntea.com/profitreport.